What the UK’s debt really means for your money

PerspectiveWith UK borrowing near record highs, we explore how government debt impacts your mortgage, investments, and financial future.

9 October 2025 | 8 minute read

Guy Foster

Chief Strategist

RBC Brewin Dolphin

Key highlights

- Government debt impacts you: understand how national debt affects your daily life and what it means for your money.

- The hidden link: discover how government borrowing connects to interest rates, inflation, and investment opportunities.

- Tough choices ahead: the difficult decisions the UK faces to stabilise debt and how they could affect your financial future.

Britain’s national debt has reached its highest level since World War II, at 96.1% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[1] But what does that actually mean for you?

Government debt isn’t just a big picture issue – it directly influences the financial decisions that shape your everyday life, from taxes and mortgage rates to investment returns.

Let’s explore how it works and why it matters.

Why government debt matters to your finances

Public finances affect our lives in ways we don’t always notice. The taxes you pay, the public services you use, and even your mortgage rate are all shaped by government borrowing. But the impact doesn’t stop there – it can also play a direct role in your financial strategy.

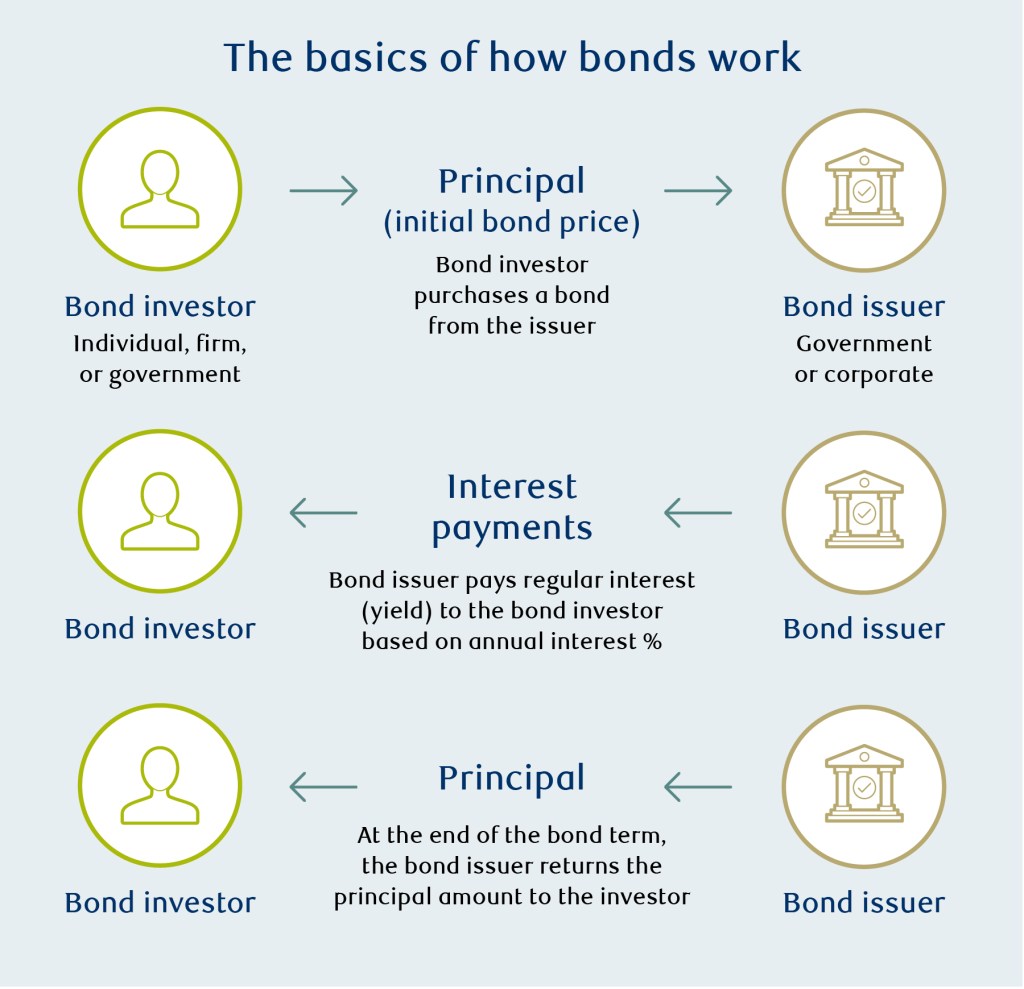

Take UK government bonds, known as gilts, for example. When the government needs to borrow money, it issues gilts, and by purchasing them, you’re effectively lending money to the government. In return, you receive regular, fixed interest payments (the yield) and the full loan amount back at the end of a set period.

This arrangement is a bit like a mortgage: borrowing at low interest rates locks in those rates for the loan’s duration. Conversely, borrowing when rates are high means committing to those higher rates until the loan matures (expires).

Bonds trade in a bond market, which works like a comparison site. It shows the interest rates available to borrowers, including the government, and the rates savers can expect to earn. Currently, the UK bond market offers higher rates than any other G7 country.

Less secure borrowers – like someone with a high loan-to-value mortgage – are charged higher interest rates, and the same principle applies to governments. For example, France pays more to borrow than Germany because it’s seen as a riskier borrower.

But government borrowing costs are usually determined by expectations about future interest rates. In the UK, where inflation is higher than in other countries, interest rates are expected to stay higher too. This results in higher bond yields – the cost the government pays to borrow money.

Higher government borrowing costs mean higher potential returns for bond investors lending to the government. But they also mean higher interest rates for other UK borrowers, such as homebuyers seeking mortgages.

Does the UK have a debt problem?

We know the UK’s higher borrowing costs are mainly due to expected interest rates, but the country’s public finances are also under strain.

When the government spends more than it collects in taxes, it runs a deficit. Over recent years, including two major global crises, these deficits have added up, pushing national debt to 96.1% of GDP. This means the UK owes almost as much as it produces in a single year.

Is this a problem?

Well, deficits are normal, particularly during economic downturns. However, large and persistent deficits can become a challenge.

That said, the UK’s historical borrowing strategy offers some short-term relief. For much of the last decade, the UK benefited from low interest rates and locked in those rates when borrowing. While the current yield on UK bonds is 4.9% (reflecting today’s higher interest rates), the government is still paying an average interest rate of just 2.3% on existing debt.

This is similar to how fixed-rate mortgages shield homeowners from immediate rate increases. So, time is on Britain’s side.

Is UK debt sustainable?

This is the key question.

Sustainable debt means avoiding it growing relative to the size of the economy. Think of it like a household mortgage: if your income grows faster than your repayments, the debt becomes easier to handle.

For governments, the same logic applies. If the growth rate is faster than the interest rate, then it makes the burden easier to shoulder.

But the UK is in a challenging position.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) warns that slowing economic growth and higher interest rates are making it harder to stabilise the national debt.

The UK’s ageing population is contributing to this slowing growth, a trend that will be compounded by limitations on inward migration. At the same time, persistent wage pressures suggest that interest rates will need to remain high.

If economic growth continues to slow while interest rates remain elevated, the government will need to find more ways to save money.

Is a crisis inevitable?

The term “fiscal crisis” might sound dramatic – where a government can no longer borrow money and faces a bailout – but the UK is far from such a scenario.

An “unsustainable” level of debt can, paradoxically, be sustained for a long time, especially for a country like the UK which borrows in its own currency and has a strong central bank. However, it does leave the country highly vulnerable to economic shocks.

A sudden loss of investor confidence, triggered by political instability or another downturn, could sharply increase borrowing costs. Without a credible plan to stabilise debt, the risk of a crisis – and the cost of fixing one – grows.

What can be done?

In short, there’s no easy fix. In the last digital issue of Perspective, we explored some of the ways the UK could potentially unlock growth. More broadly, though, achieving fiscal stability comes with difficult choices:

- Raise taxes: already at post-war highs, further increases could discourage work and investment, stifling economic growth.

- Cut spending: public services like the NHS are under immense strain, making more cuts a monumental challenge.

- Boost economic growth: this is the most desirable option, as higher growth generates more tax revenue which reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio. Growth is also more of an aspiration than a policy.

Is tax reform likely?

Reforming the tax system could encourage growth, but it’s politically challenging. For example:

- Wealth taxes: while there is growing support, options like an annual wealth tax are difficult to implement, hard to enforce, and misguided because they discourage domestic saving and investment. Some arguments say shifting the tax burden from income to wealth, such as through pension or property tax reforms, could improve incentives.

- Property taxes: stamp duty and council tax are widely acknowledged as outdated, but reform has been avoided for decades due to political risks.

Ultimately, the UK’s tax code, with over 1,000 individual reliefs, is complex and distorts business activity.

Are there any other options?

- Inflation: in theory, higher inflation reduces the real value of government debt. However, around a quarter of the UK’s debt is index-linked, meaning it rises with inflation – limiting the benefit. Deliberately stoking inflation would also harm households, savers, and the wider economy.

- Luck: unexpectedly strong global growth, falling energy prices, or a productivity-boosting technological breakthrough – such as artificial intelligence – could improve the outlook. However, slowing population growth and rising taxes could have the opposite effect. Relying on luck is also an imprudent strategy.

What does this mean for your money?

Government debt might seem abstract, but it has real-world implications for your personal finances, including:

- Taxes: higher debt could lead to higher taxes to cover borrowing costs.

- Mortgage rates: rising interest rates may make mortgages and loans more expensive.

- Investments: UK government bonds could offer attractive returns in the current environment, but rising inflation might impact the value of your portfolio.

The road ahead

The UK’s public finances are at an important juncture. High debt, persistent deficits, and rising borrowing costs create a difficult environment.

For investors, these higher costs present opportunities, especially with the tax-efficient benefits of gilts. But they may also increase pressure on taxpayers.

Smart financial planning is key, and we’re here to support you. We can structure your portfolio to manage risks, optimise tax reliefs, and help safeguard your wealth. With upcoming government decisions likely to impact your finances, we’ll guide you through the challenges and opportunities.

Speak with your wealth manager today to help secure and grow your financial future.

About the author

Guy Foster

Chief Strategist

Guy previously served as Head of Research before becoming Chief Strategist. He is responsible for overseeing investment strategy, offering tactical investment recommendations to our investment managers, and leading the Investment Solutions business.

[1] As at 31 July 2025, Office for National Statistics

The value of investments, and any income from them, can fall and you may get back less than you invested. This does not constitute tax or legal advice. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each client and may be subject to change in the future. You should always check the tax implications with an accountant or tax specialist. Neither simulated nor actual past performance are reliable indicators of future performance. Information is provided only as an example and is not a recommendation to pursue a particular strategy. Information contained in this document is believed to be reliable and accurate, but without further investigation cannot be warranted as to accuracy or completeness. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.